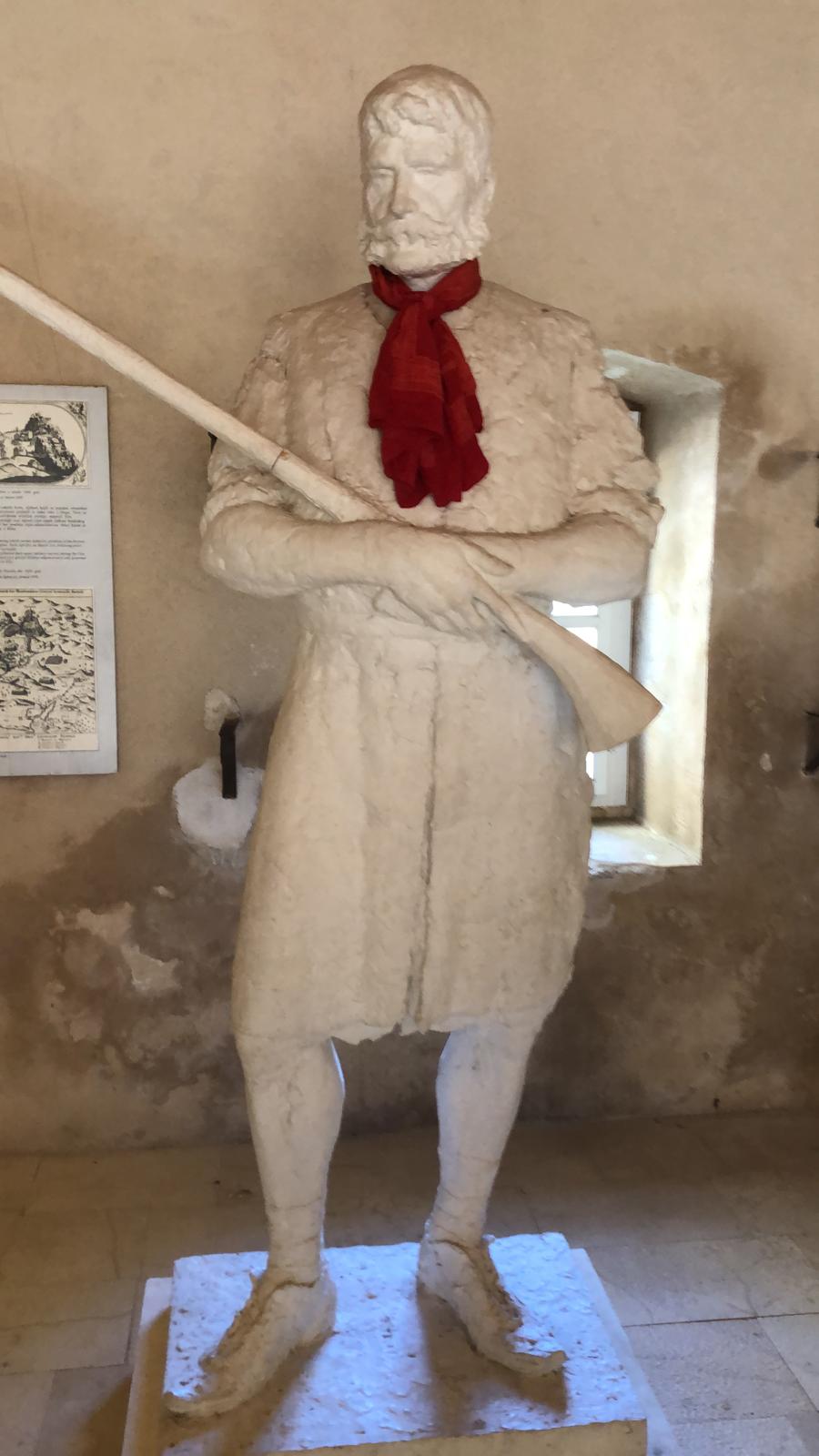

Petar Kružić was most probably a native of Krug in Nebljuh, district of Lapačka County. Later, chroniclers and historians, mostly for localpatriotic reasons, tried to appropriate and present him as one of their countrymen because he enjoyed incredible popularity as an anti-Ottoman warrior.

Petar Kružić was most probably a native of Krug in Nebljuh, district of Lapačka County. Later, chroniclers and historians, mostly for localpatriotic reasons, tried to appropriate and present him as one of their countrymen because he enjoyed incredible popularity as an anti-Ottoman warrior.

Therefore, Johann Weikhard Valvasor emphasized that Petar Kružić was the Lord of Lupoglav in northern Istria, and Pavao Ritter Vitezović claimed that Kružić was a native of Trsat. Andrija Kačić Miošić believed that Kružić originated from Poljica, old Croatian district near Klis. Even Radoslav Lupašić, while accepting the opinion of his contemporary historians that Kružić's native land was area of medieval Nebljuh, did not resist temptation to mention his hometown's folk tradition by which Kružić was born in fortress Zvečaj located on the shore of river Mrežnica near Bosiljevo.

At the beginning of the century (1513), Petar Kružić was already in Klis, performing a certain military duty - it is believed that he was vice-castellan. Ottomans raised the first serious siege of Klis in 1515 under leadership of Skender-Bey Ornosović. This attempt did not come to fruition, so Ottomans came again to conquer Klis after several years, precisely in 1520. This time they found "Captain and Knez of Klis" Petar Kružić in charge of Klis and their intentions were ruined once again (knez is a medieval title used in Croatia, equivalent of duke, count or prince). Klis was under a siege again next year, but in the end Makut Pasha had to withdraw with his 2000 soldiers and had to satisfy with burning and plundering of the suburbs. In 1522, Hasan Pasha from Mostar and Mehmed-Bey, Herzegovinian sanjak-bey, have met another defeat. Brave Petar Novaković of Poljica have repressed their forces with only three hundred defenders. Soon Ottomans, who got a new sanjak-bey, began more extensive preparations for conquest of Klis. In 1524, Mehmed-Bey Mihalbegović decided to break down all resistance that Uskoks of the royal town Klis were giving to Ottoman army that was not accustomed to suffering defeats, especially at the time of great sultan invaders Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent. Mehmed-Bey sent his deputy Mustafa with nearly 3000 soldiers to besiege Klis, commencing a several-month siege.

Kružić was trying to secure support for Klis defenders through diplomatic channels. He was seeking resources in money, food and soldiers in the courts of other European Christian nations that were in greatest danger from Ottomans if Klis would fall. Considering that Klis was a royal town under the rule of Croatian-Hungarian Kingdom, Kružić and Klis defenders were in service of Croatian-Hungarian king. Therefore, Kružić frequently went to Croatian-Hungarian ruler to acquire promised salary, funds and defence aid. However, except empty promises and words of praise for such a fierce opposition to Ottomans, he would never get what he deserved and what was necessary for the defence. Only Pope have been sending aid from Vatican to Kružić and Klis defenders.

Kružić was trying to secure support for Klis defenders through diplomatic channels. He was seeking resources in money, food and soldiers in the courts of other European Christian nations that were in greatest danger from Ottomans if Klis would fall. Considering that Klis was a royal town under the rule of Croatian-Hungarian Kingdom, Kružić and Klis defenders were in service of Croatian-Hungarian king. Therefore, Kružić frequently went to Croatian-Hungarian ruler to acquire promised salary, funds and defence aid. However, except empty promises and words of praise for such a fierce opposition to Ottomans, he would never get what he deserved and what was necessary for the defence. Only Pope have been sending aid from Vatican to Kružić and Klis defenders.

Besides Klis, Kružić governed and defended other towns and fortresses on Croatian border with the Ottoman Empire. Such was Senj (another uskok town) with fortress Nehaj. Kružić was sharing Senj captainship with his brother in arms and friend Grgur Orlovčić. Kružić broke the mentioned siege of Klis in 1524 by leading Grgur Orlovčić and a thousand and five hundred soldiers from Senj to Klis on forty ships. Kružić and Orlovčić charged through Ottoman lines and liberated Klis of the Ottoman siege, seizing three Ottoman cannons in process. However, after these great victories, troubles have just started for Croatian people.

Besides Klis, Kružić governed and defended other towns and fortresses on Croatian border with the Ottoman Empire. Such was Senj (another uskok town) with fortress Nehaj. Kružić was sharing Senj captainship with his brother in arms and friend Grgur Orlovčić. Kružić broke the mentioned siege of Klis in 1524 by leading Grgur Orlovčić and a thousand and five hundred soldiers from Senj to Klis on forty ships. Kružić and Orlovčić charged through Ottoman lines and liberated Klis of the Ottoman siege, seizing three Ottoman cannons in process. However, after these great victories, troubles have just started for Croatian people.

John Zápolya, former rival of King Matthias Corvinus, was once again heavily involved in politics. Many Croatians have been dissatisfied with the rule of Ludovik II. Jagelović since he was a weak ruler who could not confront Suleiman I. After August 29, 1526, it became clear that Croatia would not be able to defend itself from Ottoman army without help of other countries. Namely, Ludovik II. was defeated in Battle of Mohács. He died fleeing away, and a lot of Croatian knights and nobles were killed in the battle, including Grgur Orlovčić. After this great defeat, when the second generation of Croatian nobility (Battle of Krbava Field and Battle of Mohács in time period of 31 years) was lost, Croats were choosing their new king and were divided between themselves on that subject once again. A part chose aged John Zápolya for the king and other part chose Ferdinand Habsburg. Therefore, there was a civil war.

In that rift and war struggle, Kružić had to finance and take care of Klis defence himself. He has asked Ferdinand to help him or to release him of the services, but Ferdinand has refused and, as well as his predecessor, continued with empty promises of aid for Klis. Kružić had to remain true to the crown and defend uskok towns: Klis and Senj.

In that rift and war struggle, Kružić had to finance and take care of Klis defence himself. He has asked Ferdinand to help him or to release him of the services, but Ferdinand has refused and, as well as his predecessor, continued with empty promises of aid for Klis. Kružić had to remain true to the crown and defend uskok towns: Klis and Senj.

Seeing that Klis was not getting any help, Husref-Bey demanded (1528) of Klis defenders to surrender the town, but it was resolutely rejected. Then, the famous Megdan (duel) between Miloš Parižević and Ottoman Bakota occurred on the Parh field, north of Klis Fortress. Stakes were high. If Bakota won, Uskoks would surrender and leave the fortress to the Ottomans. On the other hand, if Parižević was victorious, Ottomans would end the siege. Parižević was slim, fast and agile, and Bakota was robust, strong and powerful. At the end of the great duel, Parižević triumphed over Bakota and became a legend. In memory of his victory, the area in Klis where they fought is today still called Megdan.

Kružić had enemies in Ottomans, and in Venetians, and in shortage of ammunition, food and money, and the king did not provide him any aid. Ottomans, noticing that Klis could fall into their hands, undertook important work of building towers on the paths to Klis in 1530. In Konjsko, a village north of Klis, a tower was built in which they intended to place reserve troops and prevent communication between Klis and Neorić at same time. The second tower was built in Grlo, most probably erected in the area formerly called Viskatac, and was located in a place that controlled passage between Mosor and Kozjak, as well as oversaw former caravan route. The third tower (today: Kulina) was constructed at Kozjak above a place that today bears patronymic names Odžići and Meštrovići. This, today almost collapsed, round tower oversaw road (very narrow and always difficult to pass) that led from Zagora to Solin. Kružić and Uskoks could still pass to Kaštela and Solin, and retreat or surrender.

Toma Niger, Bishop of Trogir, was bringing food and ammunition and helped the town's defence. After Orlovčić's death, he remained the only strong support to Kružić's efforts. However, next year (1531), noticing that now it was possible to encircle Klis from all sides, Husref-Bey built a fort on the eastern Salona walls. With that fort constructed, all paths from Klis to Split were blocked. Malkoč-Bey, commander of the Solin fort, supplied it well expecting Kružić to attack there first.

Venetian Nicola Querini tried to take advantage of the situation and seize Klis in 1532. While Kružić was not in Klis, he has managed to persuade a part of Klis defenders to let Venetians into the town to defend themselves together from the Ottomans. Immediately after his soldiers entered Klis, he ordered vice-captain Cimbrić, priest Šimun and a part of warriors who were faithful to Kružić, to leave the town. Kružić found out that Klis was in hands of Nicola Querini in Ancona while returning from Pope Clement VII. He gathered the exiled Klis warriors and set out to re-take Klis. Even before Kružić has arrived in Klis, people rebelled against Querini because he did not do anything against Ottomans. Evenmore, he had an agreement with them and even planned to bring Ottomans into Klis. So, people drove out Querini and the Venetians, and returned Klis to their own control. Later, Kružić arrived to Vranjic harbour with his warriors. They fiercely and quickly attacked the Ottomans, defeated them and finally the siege was broken. Kružić and his warriors were welcomed in Klis with great joy and celebration. It was an extraordinary victory for Kružić and Klis defenders who have once again managed to resist all attempts of the enemies.

Venetian Nicola Querini tried to take advantage of the situation and seize Klis in 1532. While Kružić was not in Klis, he has managed to persuade a part of Klis defenders to let Venetians into the town to defend themselves together from the Ottomans. Immediately after his soldiers entered Klis, he ordered vice-captain Cimbrić, priest Šimun and a part of warriors who were faithful to Kružić, to leave the town. Kružić found out that Klis was in hands of Nicola Querini in Ancona while returning from Pope Clement VII. He gathered the exiled Klis warriors and set out to re-take Klis. Even before Kružić has arrived in Klis, people rebelled against Querini because he did not do anything against Ottomans. Evenmore, he had an agreement with them and even planned to bring Ottomans into Klis. So, people drove out Querini and the Venetians, and returned Klis to their own control. Later, Kružić arrived to Vranjic harbour with his warriors. They fiercely and quickly attacked the Ottomans, defeated them and finally the siege was broken. Kružić and his warriors were welcomed in Klis with great joy and celebration. It was an extraordinary victory for Kružić and Klis defenders who have once again managed to resist all attempts of the enemies.

However, the Ottoman tower in Solin has still bothered Kružić. Therefore, on September 17, 1532, he attacked this tower, conquered it and destroyed it completely by cannons, so that Ottomans could no longer block the road from Klis to the sea. After that, Kružić led an attack on fort Čačvina, which was under the Ottoman rule, broke into it, and burned it. These successes of Kružić and his Uskoks earned them a great reputation among people who started to believe that Kružić could succeed in defending Croatia from Ottoman attacks. There were less and less people escaping from endangered places, and these guerrilla ventures have strengthened Kružić's captaincy, and he inspired numerous new warriors, associates and comrades to join his efforts. However, Ottoman army did not intend to give up Klis because Istanbul strategists saw it as foundation for a permanent rule over central Dalmatia. That is why, in 1534, Mehmed-Bey Mihalbegović (Bosnian sanjak-bey) and Piri-Bey (Herzegovinian sanjak-bey) bombarded Klis Fortress from cannons for a month, but again could not conquer Klis.

Next year (1535), at the beginning of February, Ottomans tried to seize Klis with old tactics - bribery, but again they did not succeed. In 1536, they experienced another defeat in a row even though they have had help of Venetian Split Duke Urban Bollani. In September of the same year, Gazi Husref-Bey led an Ottoman army that rebuilt the tower above Ozrna (east of Klis Fortress), erected the destroyed fortress in Solin Gradina, and built a third tower in Kučine (below Mosor, east of Klis) which has blocked passage via Mosor to Stobreč and Kamen. While Ottoman army was building forts, blocking paths to Klis, burning fields and enslaving population, Kružić was away trying to acquire food, ammunition and soldiers for Klis.

Next year (1535), at the beginning of February, Ottomans tried to seize Klis with old tactics - bribery, but again they did not succeed. In 1536, they experienced another defeat in a row even though they have had help of Venetian Split Duke Urban Bollani. In September of the same year, Gazi Husref-Bey led an Ottoman army that rebuilt the tower above Ozrna (east of Klis Fortress), erected the destroyed fortress in Solin Gradina, and built a third tower in Kučine (below Mosor, east of Klis) which has blocked passage via Mosor to Stobreč and Kamen. While Ottoman army was building forts, blocking paths to Klis, burning fields and enslaving population, Kružić was away trying to acquire food, ammunition and soldiers for Klis.

The 1537th began with a terrible winter. There was inconsiderable amount of food and little ammunition left in Klis, and the moral of the defenders was getting lower. They also had to fight for water since Ottomans have occupied all sources of drinking water that were out of the town (Belimovača, Tri kralja, Bađana, Ilijino vrilo), and water cisterns in the fortress have not been enough for the people and horses.

Kružić then received so needed aid from King Ferdinand for the first time ever. The king sent him soldiers-mercenaries to help in the defence. Thus, Kružić set out from Senj to defend Klis with several Uskoks, the soldiers-mercenaries of King Ferdinand and seven hundred papal soldiers, in total a little less than 3000 soldiers. In night between 11 and 12 March 1537 (at the eve of Saint Gregory), Kružić disembarked unnoticed in Vranjic harbour, leading the help to Klis, the town he had been defending for more than twenty years. In order to break the Ottoman siege, he first had to conquer the forts around Klis. In the first attack, he destroyed the forts at Ozrna and Kučine, and afterward stormed to Solin Gradina. Then, Murat-Bey Tardić and Malkoč-Bey arrived with 2000 Ottoman horsemen and some infantry and attacked Kružić's army.

The foreign mercenaries, when they saw the Ottoman cavalry, immediately fled fearfully to the ships. Kružić was trying to hold battle formation and fought shoulder to shoulder with few of his Uskoks. With his two hundred warriors, he fought against ten times greater enemy force, who was constantly pushing them toward the ships. In the last moment, everyone boarded the ships. However, the ship was overcrowded with people and equipment so it stranded at sand seafloor and could not set sail. The Ottomans took advantage and attacked again. In the occurred melee, Atli-aga killed Petra Kružić and beheaded him. Murat-Bey Tardić stuck Kružić's head on spear and triumphantly presented it to the defenders in Klis Fortress.

After seeing their captain dead, Klis Uskoks were discouraged and decided to negotiate with the Ottomans. They agreed to give over the fortress and town Klis to the Ottomans, and the Ottomans agreed to let them, their women and children, depart undisturbed to other Croatian lands. Most of them went to Senj, the other uskok town, and continued fighting Ottomans in decades that followed (learn more - About Uskoks).

Kružić was buried in the Church of Blessed Virgin Mary in Trsat, where his head was also placed after his sister Mary had redeemed it from the Ottomans. Namely, in 1531, Petar Kružić provided building of stairs from Rijeka to the church of Our Lady of Trsat, one of the oldest Croatian Marian shrines. In that time, 128 stairs were built on the steepest part of the path. Other stairs were built later, so today there are 561 stairs from the foot of Sušak to the church. At the top of the stairs, today's basilica includes the chapel of St. Peter, which was erected by Kružić and in which body of the Croatian hero rests. On the tombstone under altar of St. Peter, in the church of Our Lady of Trsat stands a Latin inscription that in translation means:

Kružić was buried in the Church of Blessed Virgin Mary in Trsat, where his head was also placed after his sister Mary had redeemed it from the Ottomans. Namely, in 1531, Petar Kružić provided building of stairs from Rijeka to the church of Our Lady of Trsat, one of the oldest Croatian Marian shrines. In that time, 128 stairs were built on the steepest part of the path. Other stairs were built later, so today there are 561 stairs from the foot of Sušak to the church. At the top of the stairs, today's basilica includes the chapel of St. Peter, which was erected by Kružić and in which body of the Croatian hero rests. On the tombstone under altar of St. Peter, in the church of Our Lady of Trsat stands a Latin inscription that in translation means:

This marble stone covers the bones of Petar Kružić, whom, oh, Turks killed. While he was alive, Senj and Klis have never feared Turks. Death has taken his body, heaven has taken his soul, and his heroic deeds are spread around the world by eternal glory.

Christian Europe lost one of its greatest defenders by Kružić's death. By virtue of Kružić and his warriors, Western Europe could enjoy its security and developed economically, culturally and scientifically and enjoy new overseas property. Croatians were left only with cynical words of consolation like those King Ferdinand I. Habsburg wrote to Kružić before Kružić's death: "Know that we have long been trying to acquire help for you and that we have done all for your salvation and we firmly hope that this siege will be completely scattered and broken." After King Ferdinand had indeed sent soldiers-mercenaries to Kružić, he caused Kružić's death because Kružić, not knowing that he received cowardly soldiers, died trusting that mercenary army was worthy of fighting side by side with Croatian Uskoks.